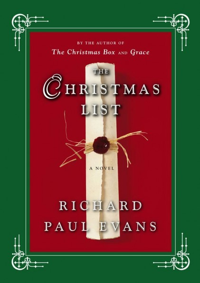

My mom got me and my siblings the same book for Christmas, a novel called The Christmas List. She thought it was a nice story and an easy read, so she wanted to share it with us. I thought maybe Sammy (9) would like me to read it with (i.e. to) him. He showed some interest, and we got started on it. After we were a few chapters in, my daughter Morgan (6) overheard us. Sammy soon lost interest, but Morgan wanted to keep listening. The last few nights that I’ve put Morgan to bed, we’ve been reading the book together. Each time I ask her if I should go on to the next chapter, she says, “Yes, don’t stop.” I usually pull the plug when I see she’s fallen asleep.

The book is not exactly a children’s book. It’s a modern-day “Scrooge” story, and it deals with some heavy themes, like death, divorce, and cancer. But it’s been a really neat way for me to connect with my daughter. She is very engaged by the storytelling, as made evident by her astute questions. She’s learning about the adult world, and we’re getting a chance to talk about it. If I ever go on too long in answering a particular question, like “What’s a lawyer?”, she’ll tell me I’ve said enough, she wasn’t really that interested, and please keep on reading.

The book is not exactly a children’s book. It’s a modern-day “Scrooge” story, and it deals with some heavy themes, like death, divorce, and cancer. But it’s been a really neat way for me to connect with my daughter. She is very engaged by the storytelling, as made evident by her astute questions. She’s learning about the adult world, and we’re getting a chance to talk about it. If I ever go on too long in answering a particular question, like “What’s a lawyer?”, she’ll tell me I’ve said enough, she wasn’t really that interested, and please keep on reading.

You never know what kinds of connections you might make with your kids or what will strike their fancy. This one caught me by surprise. I’m so impressed by Morgan’s attentiveness that it makes me want to go out and buy a bunch more of this guy’s novels to see how long I can sustain these special moments of connection.

It looks like you're new here. You may want to sign up for email alerts or subscribe to the "Lenz on Learning" RSS feed. Thanks for reading.

Sammy is getting big. He reaches past Lisa’s chin now. What they’ve always told me—that your kids will be grown before you know it—is playing out before my eyes. There’s definitely a tinge of sadness and nostalgia to seeing my kids grow up so fast. But such is the nature of life. Moments like these remind me that, if I want to enjoy my kids, I’d better get on with it now.

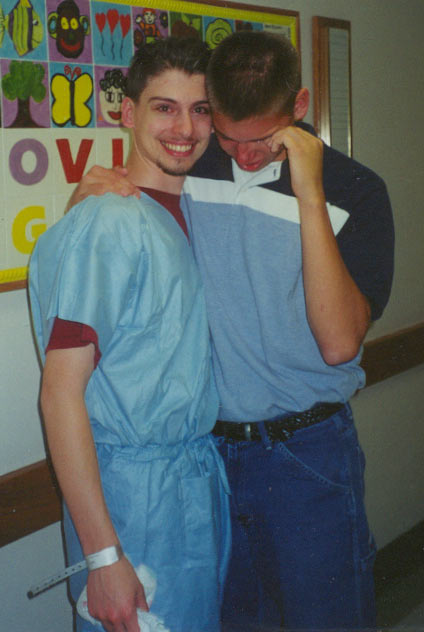

My brother and his wife are about to give birth to their first child. I can’t wait to be there to support them and celebrate with them. I remember when Sammy was born, almost 10 years ago, and my brother was right there. I have one photo in particular where he was overcome by the emotion of being an uncle for the first time:

Soon I’ll be able to share the same joy with him. I’m looking forward to it.

After writing about my frustrations around bedtime, I resolved to enjoy putting my sons to bed last night. And I’m happy to report that things went very well. All I did was change my own perspective. Rather than focusing on a particular outcome (getting them to sleep so I can go to bed), I opened my heart to whatever the evening would bring. I got myself ready for bed so that I could just fall asleep in my son’s bed if necessary. And I decided that I would relax and enjoy the time we had together.

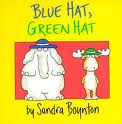

It did turn out to be very enjoyable. (What a coincidence! 😉 ) I read a book to Lucas (3). Then Lucas said he wanted to know how to read, so Sammy (9) decided to start teaching him. For about an hour, Sammy painstakingly went through every word in Blue Hat, Green Hat , and Lucas stayed attentive the entire time. Sammy got exasperated a few times (what do you expect from a 3-year-old, Sammy?), but Lucas was still enjoying himself. And so they persisted. After all of that, I think they were both a bit tuckered out.

, and Lucas stayed attentive the entire time. Sammy got exasperated a few times (what do you expect from a 3-year-old, Sammy?), but Lucas was still enjoying himself. And so they persisted. After all of that, I think they were both a bit tuckered out.

When I say it “went very well”, it wasn’t because Lucas did anything particularly different. It was because I changed my own perspective. (Ironically, he also went to sleep earlier than usual. Perhaps he was expecting to feel my normal resistance, and, finding none, just relaxed.) Even if he had stayed up extra late, my intention was still to remain calm and enjoy every moment I had with him.

Stay tuned for the next bedtime report.

Perfection of means and confusion of goals seem to characterize our age.

— Albert Einstein

I read this quote recently, and I thought how appropriately it characterizes the state of education in America. But it’s also a great thing to consider in your parenting. Are you perfecting means but confusing ends in your parenting?

This is as good a context as any to share one of my struggles/failures as a father (as I recently promised to do). I have been known to get in some really nasty moods, especially late at night, especially if I’ve been eating anything sugary. And I’ve recently seen a pattern in myself of dreading bedtime, i.e. putting our kids to bed. Morgan, my daughter, tends to be the easiest. She’s ready for bed the soonest, and she falls asleep quickly. And Sammy, my oldest son, although he takes his own sweet time (he gets that from me), is pretty cooperative too. But Lucas, who shares a room with Sammy, is my 3-year-old, and he doesn’t like going to bed, at least not lately. And I don’t like putting him to bed. In fact, I recently told my wife Lisa, “I hate bedtime.”

On more than one occasion, Lisa has had to come to relieve me, when she hears Lucas crying. In those cases, I’m tired and cranky and impatient. All I want is for him to stay in his bed and let me go to bed. I don’t want to hear any more. I don’t want to snuggle him, I don’t want to rock him, or make up any more stories. I just want to go to bed.

Fortunately, we’ve recognized the pattern and are starting to do something about it. Lisa and I will be taking turns, so neither of us gets burned out and each of us gets a break. This is a good start. Also, I’ve been attending better to my own sleep and eating habits, which helps prevent those nasty moods. As for getting Lucas to bed, we’ve even started talking about using rewards or punishments to get him to start cooperating. (Yes, I’ve read Alfie Kohn’s Punished by Rewards, and, yes, I know this is not ideal.)

This is a sad state of affairs, because bedtime can be a great time for connecting with your kids. One of the things Lisa and I both want to do is start intentionally enjoying bedtime. In other words, don’t just perfect the means of getting the ostensible end: getting the kid to sleep. But ask: what other ends, or outcomes, do we want from bedtime? If getting him to sleep were the only aim, then we may as well just drug him. (I’m kidding, sheesh!) What if bedtime was not only a time to get Lucas to sleep but also a time of connecting with him? Of hearing him and understanding him and deepening our relationship? What if a change of perspective is all that’s needed?

I don’t know what we’re going to do. We’re still figuring it out. But I’ve started to step back and ask myself, what’s really possible here? What do I really want from bedtime?

First, I love to write. Difficult though it may be, I feel much better after I’ve been able to share my thoughts or insights with others through the written word, particularly when those thoughts are fueled by passion. (And if you’ve read much of this blog, you know I’m passionate about the topic of education.)

Second, reflection on parenting makes me a better parent. When I have time to reflect on parenting, especially in a public context, it makes me feel that much more accountable for being a good parent.

Third, I want to encourage parents and help them become better at what they do. I want to help them question their own assumptions, and to make choices consciously. In this respect, I see this blog as making a modest contribution to humanity.

Fourth, I want to draw more attention to the Sudbury approach to education. Among alternative educational models, most people have heard of Montessori, and many have heard of Waldorf, but few have heard of Sudbury. I want more people to find out about what a wonderful option Sudbury schools are. I want to see more schools founded and more schools flourishing.

Finally, I want to see my kids’ own school, The Trillium School, continue to succeed. I want my kids to have this option for the full length of their school-age years. This blog will help existing parents of Trillium to stay stimulated and on board. And, by helping spread the word about educational alternatives, it may indirectly draw more local parents into considering Trillium.

Whatever your interest in reading this blog, thank you. Now that I’ve shared why I’m writing this blog, would you be willing to leave a comment, sharing why you’re reading it?

I’ve fallen off the blogging horse for the last two weeks, and now it’s time to get back on. I ran out of pre-written articles, and I haven’t been writing new ones consistently. Two things will help me move forward:

- Setting aside a particular time of the day to focus on writing

- Continuing to let go of perfectionism in both writing and parenting

Perfectionism has always been an issue for me. If I don’t have something written perfectly or thought through perfectly, I tend to get stuck. Writing has always been difficult for me, but as I’ve learned to let go of perfectionism, things have gotten easier. I’ve embraced this mantra: “Done is better than perfect.”

Bloggers lead double lives. There’s the life we live on the Web—our online persona (perhaps one of many). And then there’s the real, day-to-day life we live at home and at work. It’s funny how a book, or even a blog post, creates a static representation of an author in the reader’s mind, since that may be all they have to go on. When reading a self-help book by an “expert” on self-help, we assume that the author is probably a high-functioning person, having mastered and applied the techniques they espouse. Or when reading a book about spirituality, we assume that the deep insights therein come from a person who is spiritually grounded, devoted to God, [insert whatever ideal picture of spirituality you have]. And clearly, for someone to have such insights, they have to have been in touch with a truth that’s greater than themselves. But the thing I unconsciously forget is that they’re people, just like me. They might be getting old. They may die soon. They may be going through a tough time. They may be “backsliding”. They may have been failing. The point is that they’re changing, and the book they wrote is just a snapshot of what they were thinking at a particular time in their life. The book may be quite popular, and the book itself doesn’t change. But as soon as it’s published, the writer and the book begin separate lives. The writer goes onto live their real life, perhaps writing more books, or perhaps not, but in any case, the writer is not the book. In a certain sense, this is so patently obvious that it seems silly to be saying it. But I have to remind my less-than-conscious mind not to equate a book with its author.

I think that one of the reasons I haven’t been blogging is that I feel like I haven’t been a very good parent lately. And I have this (increasingly conscious) belief that, to write about something, you must be an authority on the topic, or at least you must practice what you preach. And I accept that these are good principles to follow. But what do you do when you fail to practice what you preach? Or when you start feeling like you don’t know what you’re talking about? Is the only option to stop writing? (That’s what I’ve done.) No, I don’t think so.

I think there’s another option that has integrity and that can create value for readers. Of course, it’s easy enough to think of options that have neither. (Keep on B.S.-ing to sell more books. Live a double life. Pretend you’re something you’re not.) And we all know that the world has no shortage of pointless blogs. I think the key is simply this: honesty. Let people know you’re not perfect. That way they’ll relate to you better. Share what you can, even if it isn’t already perfectly thought through. People may still yield some benefit from what you have to say.

So now I’m doing something to overcome both of the things that were blocking me: lack of a scheduled time for writing, and perfectionism. First, I now have someone keeping me accountable for writing during the times that I say I’m going to write. And second, I’m going to start sharing about my failures as a father, not just my successes. And maybe get more, ahem, personal.

My friend Elsa recently wrote this response to my “Bullying” article. I wanted to repeat it here, because it adds some needed perspective to the negative picture I painted. I’ve also included my response below.

That’s a very interesting story, and oddly almost the opposite of what I experienced when I transitioned for an alternative program to a public high school. Going in I was very nervous about other kids and what they might say or do… I feel like I may have seen too many horror stories on after school specials. Thankfully I was pleasantly surprised. Despite the fact that all my classes were with total strangers, I felt very welcomed by my school community. I made new friends, and people were by and large very nice to me. It saddens me to hear about those painful times you went through, but I think you might be giving high schoolers too much of a bad rap. In my experience we are generally a lot nicer than people give us credit for. I was not ostracized when I transferred in from that strange hippy school called options. I hope that your story is the exception rather than the rule. I’ve really enjoyed my high school, and the people I’ve met there.

Hi Elsa, thanks so much for your comments. I think you’re probably right that this post could mislead people by painting too negative a picture of high school. It wasn’t as if everyone was mean. I made some good friends in my 3 years in high school. The vast majority of kids were friendly and nice to me. It’s unfortunate that only a couple of people (one in particular) could have such a negative influence on my overall experience.

I’ll reflect some more on my high school experience. Apart from bullying, I still wasn’t particularly impressed by the experience. I can think of some peak moments, like reciting Hamlet soliloquies for my English class (and happily accepting my teacher’s offer to swap more performances for incompleted book reports). A field trip to Ashland for the Shakespeare festival (with that same class) also stands out as really positive. But these were really hit-and-miss. The majority of the time, I was bored and unimpressed. And there are a few bitter memories, such as when my advisor talked me out of skipping a grade of math, or when my joke of a biology teacher (who later got fired for inappropriate relations with a female student) told me “you think too muchâ€. Or when I got my first B, in traffic safety of all things. Oops, I’m lapsing into negativity again, sorry.

I finally got through it all and went off to college, where in my first year, I matured more than all those three years of high school combined. When I compare my high school and college experiences, they’re like night and day. I knew I was in for a different experience when my academic advisor in college didn’t hesitate one moment to let me jump right into the upper-level “History of Philosophy†course as a Freshman just because I wanted to! I intend to go back to school one day (and never return, moving into an academic career). For all my love of academia, you have to wonder why I’m so negative on high school and everything preceding it. I think it comes down to the forced aspect of public education. Generally, college students are there because they choose to (although I fear that’s changing too these days).

I’m glad that you’re flourishing in high school, both academically and socially. And I know that you want to be there. And I’m especially glad that your transition to high school was the opposite of mine (a relief instead of an ambush).

Hey Evan,

Here’s an interesting blog post on math education I thought you might be interested in:

How Good Are UW Students in Math?

Brian

Hi Brian,

That was interesting and challenging, and a reminder of how far I’ve drifted from mainstream educational philosophy. Thanks for sharing it.

Math education is hard, because only some kids are interested in what’s being presented when it’s being presented. I remember just plowing through my Algebra textbook (before going to public high school). I was interested and ready and it was fun (even though I didn’t really connect it to anything useful other than doing math assignments). But when it’s a required thing, and the student isn’t interested, it’s a major uphill battle. Extend it for 12 years and it only gets worse. Regardless of what textbook is used, forced education is a messy, brute-force approach. I think it does more harm than good, totally killing whatever interest such people might otherwise have developed when they were ready.

I also think that the doomsday tone around poor math skills is blown way out of proportion. Dichotomies involving burger-flipping are ridiculous. Perhaps as a society we need to start releasing our death grip on the failing enterprise that is standardized education, and a let a rebirth happen. We should stop assuming we know everything future generations will need to know. Also, average math skills as determined by standardized tests are a poor indicator of our country’s capacity for innovation in science and other areas of inquiry. Great minds produce innovation and discovery, and they hardly depend on having learned the same thing as everyone else. Yet that’s what our education system is about—trying to ensure that everyone learns the same things at the same time. That’s a good recipe for killing innovation: mass homogenization.

Have you ever read “A Mathematician’s Lament”? I re-read it just now. It’s really eye-opening, a delight to read, and makes me want to do real math.

A Mathematician’s Lament (PDF)

You should read the whole thing when you get a chance, but this much shorter article has some highlights:

Simple Math

Thanks again for the link,

Evan

P.S. I recently realized that school (including my algebra course) trained me to hate puzzles (not the jigsaw kind). I have a strong aversion to them if there’s not a right answer or if the procedure for getting to it isn’t right in front of me. Only recently have I allowed myself to develop some comfort around conundrums. Enjoyment comes next…

This afternoon, I had my first PlayTime session with my oldest son (9). He really wanted to make it happen today, so even though we were home alone with his younger brother (3), he made sure we’d be able to do it by getting the little one occupied with a cartoon on the computer and then sneaking out with me.

He quickly came up with an idea for some role-playing. We both found ourselves stuck inside a massive labyrinth with all sorts of nooks and crannies and walls and hidden doors and chutes and stairways. We had to be careful not to step on any floor tiles that released arrows or trap doors. Our task was to find our way out. Along the way, we came across strange creatures (played by our kittens) that looked benign but actually secreted dangerous green slime. We also came across a room full of treasure, and we almost met our doom when the treasure became so alluring as to make us mad with greed, losing our minds. In one case, I saved him; then it was my turn to be weak, and he saved me. We also changed size several times, whirled our way across dimensions in a magic elevator, and narrowly escaped being eaten by a 10-headed monster with 40,000 arms.

At one point, I had him laughing hysterically, and, in accordance with Cohen’s advice in Chapter 5 (“Follow the Giggles”), I tried to see how long I could sustain it. After cracking up and saying, “That was hysterical,” my son told me, “Okay, let’s get back to the game.” Heh, I was making him laugh, yes, but I was getting off task. I’m clearly still learning.

We started at 3:49pm, so I thought to myself, “We’ll wrap it up at 4:20,” rounding up to the nearest 10. But I was so exhausted by the time 4:18 came around, I was thinking 4:19 would be a good stopping point after all. As it happens, when he saw it was just about time to finish, we extended it slightly and wrapped things up nicely at 4:23pm. We made ourselves wake up from our dream and found ourselves lying on the floor, grateful to be safe and at home.

Thanks to Bethany for suggesting the Playful Parenting book, by Lawrence Cohen, in response to my “Connecting with my kids” post. I’ve now skimmed most of the book, and my wife has read the entire thing and enjoyed it.

We’re interested in trying out one technique in particular. In chapter 9, “Follow Your Child’s Lead,” Cohen introduces “PlayTime,” a scheduled, more intense form of playing with your kids where you make an explicit, concerted effort to follow their lead, wherever they want to go, for a specific period of time.

The basic format of PlayTime is quite simple. The parent or some other adult sets aside regular one-on-one time with a child. The adult offers the child undivided attention with no interruptions and with a clear focus on connection, engagement, and interaction. In a sense, PlayTime is just Playful Parenting Plus, where the “plus” means more enthusiasm, more joining, more commitment to closeness and confidence, more fun, a more welcoming attitude toward their feelings, more willingness to put one’s own feelings aside, more active and boisterous play. In addition, you don’t answer the phone or cook dinner or take a nap during PlayTime.

One of the things that attracts me to this particular technique is that it is a commitment for a specific period of time. It is “time-boxed.” I get to go all-out, knowing that I don’t need to worry about pacing myself beyond the agreed-upon length of time. It’s a safe way to start building my playing muscles. A high-weight/low-rep strength training program. At least that’s one way to look at it. And I don’t have to feel guilty when I’m not doing it all the time.

Another thing I like about it is how much the kids will love it. We’ll be upfront with them about what we want to do. And we’re going to schedule specific times. With two parents and three kids, that’s six sessions total. We’re going to cover each of these once a week. And we’re starting with a 30-minute period. That may seem short, but we want to be realistic.

During PlayTime, I’ll let my child know that what we do is entirely up to them. I’ll follow along, infusing the play with whatever energy I can muster. And I’ll let them remain in charge for the duration. It will be hard work but it will also be rewarding. We’re going to forge some nice connections, and I’ll have a chance to get some deeper glimpses into each of my children’s worlds.

After I’ve had some chances to try this, I’ll be reporting back on my experiences. Stay tuned.

I was reading in a devotional classic this morning and came across some analogies for the spiritual life that I think work equally well for education. Given some basic nurture, sunshine, and rain, a plant grows without any special effort or help. We can try to help it along by adding supports and scaffolding, but it will grow regardless—sometimes in spite of our interventions. We may even deceive ourselves into thinking that our special efforts were essential—that, had we not intervened, the plant would have collapsed and died. Similarly, for a child to grow taller requires no special effort.

There is no effort in the growing of a child or of a lily. They do not toil nor spin, they do not stretch nor strain, they do not make any effort of any kind to grow; they are not conscious even that they are growing; but by an inward life principle, and through the nurturing care of God’s providence, and the fostering of caretaker or gardener, by the heat of the sun and the falling of the rain, they grow and grow.

To act in ignorance of this truth would, of course, look pretty funny:

Imagine a child possessed of the monomania that he would not grow unless he made some personal effort after it, and who should insist upon a combination of rope and pulleys whereby to stretch himself up to the desired height. He might, it is true, spend his days and years in a weary strain, but after all there would be no change in the inexorable fact, “No man by taking thought can add one cubit unto his statureâ€; and his years of labor would be only wasted, if they did not really hinder the longed-for end.

Imagine a lily trying to clothe itself in beautiful colors and graceful lines, stretching its leaves and stems to make them grow, and seeking to manage the clouds and the sunshine, that its needs might be all judiciously supplied!

I think this perfectly describes how silly we as a culture look in our preoccupation with beefing up our efforts at educating children—more standards, more tests, more money. It wouldn’t be so silly if our efforts were focused on providing the basics of a nurturing environment in which kids could grow. But the drive is for much more than that. We as a society possess the “monomania” that children won’t learn anything unless we do something. And thus we have the “combination of rope and pulleys” that makes up our school system, and we debate endlessly about which ropes and which pulleys are best suited to the task. Few question whether the ropes and pulleys are necessary.

This widespread paranoia would be amusing if it didn’t exact itself so acutely on our children, each of whom must resultantly “spend his days and years in a weary strain.”

Following on my last post’s more theoretical bent, this post contains some practical advice for parents of kids who are learning to read. Most of these tips would classify as common sense if it were not for the silly psychological complexes we’ve built up as a society around how we’ll ever get kids to learn.

Read to them

Read to your kids, at least occasionally. If you want to enjoy a wealth of children’s literature (as I do), do it a lot. (But don’t beat yourself up if you only do it occasionally. It’s not as if they won’t encounter written language if you don’t read to them constantly.) Share the joy of reading with them. Don’t burden yourself with theories of reading pedagogy. Likewise, don’t assume you actually know how people learn to read. None of us really do, no matter how many letters we have after our name.

Try not to get too giddy

Seeing your kids choose to read and start making sense of things is so much fun. Soak in it and enjoy it, just as you enjoyed your baby’s first steps and their first words. But don’t praise them too much. Let it be, for them, their own enjoyable experience of reading, and not primarily a way of pleasing Mommy or Daddy.

Be a helpful resource

If your child asks you what a particular word is, simply tell them. Don’t ignore their request and instead tell them to “sound it out” (unless they’re actually asking “Can you help me sound it out?”). If you ignore their request and instead make your own demands, you’re hijacking their experience for your own purposes. Aim instead to facilitate the flow. The more they flow, the more they’ll pick up. The more you frustrate them, the less they’ll want to do it.

Let mistakes slide

The fear of letting children make mistakes while learning to read is laughable. We learn from mistakes, and it’s no less true in reading. Don’t overly concern yourself with perfection. Let words slide here and there. Again, try not to interrupt the flow experience. They’ll work out the details in the long run.

Fight your tendency to control the learning process

(As if you had the power.) Here’s an exercise for you. This is for your own good, not your kid’s (though they’ll be just fine, I promise you.) The next time they read a word incorrectly and keep going, let them do it. See how many times you can let them go without correcting them. You may have to fight with all your might that internal perfectionist, but it will be good for you. You’re giving yourself a wider range of behaviors to choose from, rather than just kneejerk reactions. The next time you correct them, it will be because you chose to, not because you were compelled to.

Summary

When your kids are reading to you, give them what they ask for, and try not to interrupt them. In short, relax and be courteous.

My 6-year-old daughter recently started showing an interest in reading the Storybook Treasury of Dick and Jane and Friends. I had bought it several years ago when looking at various approaches to teaching reading. But long since then, my wife and I had decided to let the kids come to reading on their own, when they’re interested and ready. We’ve avoided any parent-driven techniques and schedules for learning to read.

In fact, I had half a mind to get rid of the Dick and Jane book. It’s so obviously designed for teaching reading, as opposed to having any literary merit of its own. Even so, my daughter is eating it up. She delights in the pictures and uses them to sleuth out the meanings of the words. So I won’t be getting rid of it any time soon.

It’s fascinating to see how different kids learn to read. Some are more apt to “sound words out” based on what they’ve picked up about the different letter sounds. Others begin by learning specific words as a whole and later recognizing them by sight. It’s pretty obvious that my daughter does the latter. She’ll see “funny” and say “silly”, which tells me she’s not sounding things out. She’s going straight from image to meaning, even if she uses the wrong word.

Of course, such categories oversimplify things. In reality, each child uses a variety of ways to learn to read. Not only that, but each word is learned in its own unique way. Each word is first encountered in a particular context and has uniquely personal meanings. How “home” gets wired into the brain is not going to be the same as how “and” gets wired into the brain. “Home” can have all sorts of connotations; perhaps “home” is a lot more meaningful than a utility word like “and”. Then again, my daughter is particularly fond of “and”. She used to point out every instance she could find during bedtime story reading. She associated “and” with the delight of recognition and discovery.

If my observations seem to ignore all the various learning style theories and methodologies for teaching reading, that’s intentional. I’ve done a fair amount of reading about reading. But I’ve never been particularly impressed. My overall response to the massive amount of literature about reading pedagogy is “what a waste”. The underlying assumption of the whole field seems to be this: The better we understand how people learn to read, the better we’ll be able to ensure they do it. Hey, that sounds pretty reasonable at face value. But it assumes two things:

- We actually can understand how reading works

- People won’t learn to read if we don’t make them

I dispute both of these. The number of books written about the phenomenon of reading is not an effective indicator of how much we actually understand about the miracle of human communication via the written word. Theories and their resulting methodologies, such as phonics and reading by sight, are at best crude attempts to structure how human beings develop their innate capacity for communicating via written symbols. We only have little slivers of understanding about how it all works.

What’s worse is that such methodologies so often ignore what motivates people to read in the first place. And in doing so, they often destroy children’s motivation by turning reading into a required, assigned task. Regardless of how cute or fun they try to make it, reading becomes extrinsically motivated, i.e. something you do because you’re supposed to do it, not because you yourself have discovered it to be valuable.

What motivates kids to read? That’s entirely contextual and has everything to do with what interests them in general. My daughter is motivated to read about Dick and Jane and Baby Sally and Spot and Puff, because she finds all these characters adorable and she loves the pictures. Other kids first learn to read because of video games, or dinosaurs, or magicians, or baseball. It depends on the kid.

Another assumption, probably the worst of them all, is that all children should learn to read at the same age. We all know that babies learn to walk at different ages and talk at different ages. The same thing goes for kids learning to read. At Sudbury schools, where kids aren’t forced to start reading before they’re ready, kids learn to read anywhere between 4 and 11 or even 12 years old. If you’re not naturally predisposed to read before the age of 10 and you are put into a traditional classroom at the age of 6, then you’ve got a long road ahead of you, potentially filled with heartache and demeaning labels. All because of a faulty assumption.

Reading is among the many skills that kids will naturally pick up in a literate society such as ours. But we as a society don’t trust the process. We act on faulty assumptions, apply a cookie cutter approach, make reading something you must learn in school, at the same age as everyone else, and then we wonder why we have an epidemic of “learning disabilities”. Could it be we’re doing more harm than good?

Where was I? Oh yes, my daughter is learning to read. This may be the start of a real growth spurt, or it might just be a passing phase, in which case she’ll pick it up again in some other context later on. Either way, we’re going to trust the process.

How does the Sudbury school approach relate to different stages of child development? One assumption I realized I had was that children should be gradually given more and more independence as they get older. But there seems to be no such progression in the Sudbury approach. The same methodology applies to all students, ages 5 to 18. How should I adjust my thinking? Should I change my working theory of child development? Or are there components to the Sudbury approach that I’m missing?

This article seems to address my question (in an unexpected way!): “Ages Four and Up” by Daniel Greenberg, from Child Rearing. In the first paragraph, he writes:

By age four or thereabouts, human beings have a fully developed communication system which, for all intents and purposes, makes them mature persons. They are capable of expressing themselves, of understanding what’s said to them, and of structuring continuous thought; and they are capable of doing things with their environment. You could ask whether a person age four and up belongs at all in a book on child rearing, because I don’t consider someone over that age to be a child.

I probably wouldn’t go that far, but Greenberg’s assertion is worth considering. Especially when you consider how many people can go through life without seeming to mature. People don’t always act more mature the older they get. How wise and/or useful is it to declare exactly at what age a child becomes an adult? Reality doesn’t fit so nicely into such categories, whether you draw the line at 4 or 18.

On reflection, I realized that independence isn’t something we give children. It’s something they learn, regardless of what school they do or don’t attend. At a Sudbury school, kids are given the chance to develop that independence on their own schedule. The “methodology” in effect is to give them freedom externally (within a safe and caring environment), but the outcome is that they gradually develop their own internal sense of independence. So the progression is gradual, but the methodology doesn’t presume or attempt to control that progression. It just removes as many roadblocks as possible.

In contrast, the traditional schooling approach seems to encourage dependence, by filling students’ lives with activities coming from external sources (assignments, grades, schedules, etc.). Only when students are finally done with that mountain of assigned work (around age 18) do they get the freedom to start developing their own sense of independence, figuring out what they want to do with their lives, etc. Sudbury students, on the other hand, have been figuring this out all along. If their lives are full, it’s because they’ve been filling them.

I picked up a copy of David Elkind’s The Hurried Child at a used-book sale recently. Below are some quotes relevant to the focus of this blog.

What is surprising about our schools today is that they have reached full industrialization just at a time when factory work, as it was once known, is becoming as obsolete as the farmer with a horse-pulled plow.

Our schools, then, are out of synch with the larger society and represent our past rather than our future…[T]he discrepancy is particularly great today because of the knowledge explosion and the technological revolutions that occur with machine-gun rapidity. Children do poorly in school today, in part at least, because they sense the lag between what and how they are learning in school and what is happening in the rest of the world.

Consider that the above was written in 1981, long before the advent of Google, Facebook, and YouTube.

He then goes on to describe in painful detail how schools are becoming more standardized and education is becoming more product-ized. In a section called “Assembly Line Learning”, he describes the relentless pursuit to quantify children and their achievements via increasingly burdensome standardized testing.

Schools in ostrich-like fashion, are responding to the challenge of poor school performance by regression. “Back to basics.” Back to old methods and old materials. Back to a factory emphasis on worker (teacher) productivity and quality control (pupil competency) that is at odds with the major thrust of modern industry. What the traditional factory ignored and what modern industry recognizes is that the worker is not a robot, that he or she needs motivation, challenge, a sense of involvement, recognition, and some input in the system. Modern industry looks at the worker as a person, while schools, particularly those that use teacher-proof curricula do not.

Consider that the above was written in 1981, long before “No Child Left Behind”.

This all seems more true today then when Elkind wrote it. Schools are still moving backwards, and knowledge & technology are growing even faster. Do you really want to put your kids on a boat that’s sailing backwards, and anxiously hurry them along while you’re at it?

His conclusion is both gratifying and perplexing:

If we have to see our schools as factories, then we should learn from our modern-day factory experience. Hurrying workers and threatening them do not work. Treating them as human beings who want to take pride in their work, who don’t want to be confined to the same routine, and who want the opportunity to express their opinions and to have those opinions taken seriously does work…Democracy is the balance between total control and total freedom, and what we need in education, as in industry, is true democracy. Only when the values upon which this country was founded begin to permeate our educational and industrial plants will we begin to realize our full human and production potentials.

His call for democracy in education is gratifying for parents of kids at a Sudbury school. But I’m perplexed by how one would go about implementing democracy in a school run as a factory. The analogy between treating students well and treating factory workers well breaks down. Factory workers are not themselves the product being shuffled down the assembly line, whereas in schools, that’s exactly what students are. Thus a more appropriate analogy would have the widgets and cranks themselves being treated as human beings and given a say in their future, which of course is nonsense. I think the first step is to do away with the factory model. Stop treating students (i.e. people) as products, constantly assessing and assuring their “quality”.

Evenings are challenging for me. I recently committed to turning off the computer between dinner and bedtime. And now I have people holding me accountable to keeping that commitment. I’ve been so caught up in the world of work (and of setting up this blog for that matter) that I don’t know what to do with myself when I’m not in front of the computer.

I noticed something last night. (It’s probably been obvious to everyone but me.) Even when I’m spending time that’s devoted to hanging out with the kids, I habitually avoid them. Some ways of avoiding them include doing certain kinds of things with them: like watching movies, or even reading to them. You may ask: how is reading to them avoiding them? Well, for me, reading out loud is an intrinsically enjoyable and challenging activity, and it allows me to “kill two birds with one stone” when I do it in front of my children. The point is that my aim is to do something that I like doing and that the kids will go along with. While it is wonderful to see them fully engaged in listening to a story, it’s also true that I often read to them as a way of not engaging them.

In particular, I avoid playing with them. I do like board games (well, certain ones anyway). But unstructured role-playing games are exhausting to me. They’re not engaging, for whatever reason. (One reason is probably that I just haven’t exercised those “muscles” in a long time, and my imagination is atrophying.) And my oldest son has been giving me this feedback lately. “You never play games with us!” Now I’m starting to see what he’s talking about.

I probably sound like a horrible father by now. Truthfully, I am a bit horrified at the realization that I so habitually avoid engaging my kids, even while spending lots of time with them. But I’m thankful that this insight is coming while I still have a chance to do something about it. Last night, convicted of my selfishness, I worked hard at engaging the kids on their level. This time that meant being a monster who eats kids and carries them on its shoulders while looking for more “meat” to eat. All around the house. Over and over again until bed time. (I slept well last night.) As a result, I felt more connected to the kids. And last night while I was tucking him in, my 3-year-old (who hardly ever says such things) told me with a beaming smile, “I love you, Daddy” and gave me a big, fat hug. That made it all worth it.

I’ve now resolved to find more ways to lose my selfishness and connect with my kids in ways that are uniquely meaningful to them, not just me.

I’ve never written publicly about this. I was bullied in school. After a number of years homeschooling, I returned to high school in the 10th grade, as naïve as could be. No one told me not to flinch. This is a painful lesson, and you don’t get a second chance to learn it. Once you’ve flinched, it’s too late. They’ll just keep coming back for more.

Before I go on, if you’re about to enter high school, particularly if you’re coming from an alternative background, such as homeschooling, or if you’re an exchange student from another country, my one piece of advice for you is this: Don’t flinch. They’re not actually going to hit you (the first time). They’re just seeing if they can bug you, if they can put you on their short list of pathetic wimps they can have fun with. If you flinch, it’s all over. Got it? Don’t flinch.

Okay, got that off my chest. I entered 10th grade, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed. I was hopelessly introverted and nerdy, wearing a black, suede leather jacket every day regardless of the weather. I had looked forward to school. I felt pretty grown up (I was 14). But I didn’t expect people to be so mean. So I was blindsided. Fortunately, I had enough self-respect to stand up for myself and seek help with my school’s vice principal, the person traditionally in charge of student behavior problems, a.k.a. discipline. Not so fortunately, she was completely unhelpful. First of all, she tried to talk me out of doing anything about it. She made me feel like I was blowing things out of proportion. She actually tried to shame me out of bothering her. Eventually, she did something nominal, but it didn’t help. It probably made things worse.

I know that some kids had it much worse than me. And sadly, we all know how tragic the ultimate consequences can be, with incidents like Columbine. Thankfully, I was nowhere near that distraught over it. But it still wasn’t fun. This one guy used to corner me in the gym, during PE class, in that little hidden space between the corner of the room and the bleachers. Then he’d jab me in the stomach. Repeatedly. Eventually, I’d be able to find my way out and rejoin the safety of the class.

That’s the kind of thing that bullies do: inflict physical and psychological pain on people weaker than themselves. Bullies also have a strangely powerful effect on the kids being bullied. I found myself wanting to be his friend, wanting to seek approval. Ugh, it’s sick now that I think about it. But that’s the kind of effect bullies can have.

The truth of course is that I had it better off than the bullies. Think how the world must be treating someone for them to treat others so meanly. Bullies have lost whatever sense of self-respect they had. Hopefully, they’ll grow up and rediscover that self-respect, making a better life for themselves.

If you’ve been reading this blog already, you know that I blame problems like these (such as lack of respect) on school’s institutional lack of respect for its “clients”. But I don’t feel like preaching right now. I ask you to just reflect on it. When I was a kid, I actually thought that bullying was something you just had to go through, a necessary part of growing up. Now I realize that it has very little to do with my life as an adult. Sure, there are bullies in the adult world, but there’s a disproportionately high number in school. I fully reject the notion that being bullied is a necessary part of growing up. If I can help it, I’ll do whatever I can to ensure that no one else has to go through that experience, including my own children.

I’ve seen an ironic phenomenon among unschoolers (in books, blog articles, and at unschooling conferences) that I can only describe as the “unschooling thought police”. People react when certain terms aren’t used in particular, predefined ways.

“Education”

I’ve noticed that a lot of unschoolers have an aversion to the word “education” (largely due to how John Holt chose to use the word in Instead of Education). On the one hand, this is to be expected, since “education” represents so much of what unschoolers reject (compulsory, teacher-led curricula, etc.). On the other hand, it’s just a word, and traditional schools don’t have a monopoly on it. It can and does mean much more than traditional schooling. Rather than reject the word, why not reclaim it? If you’re an unschooler, wouldn’t you agree with someone who said that unschooling is a legitimate educational choice? (Or would you derail the conversation by telling your story about how you dislike the word “education”?)

“Teaching”

There’s also an aversion among unschoolers to the term “teach”, but what the aversion really represents is an underlying insight that learning does not necessarily require teaching. (In fact, it almost always doesn’t require teaching.) So rejection of the term “teach” is a crude reaction to the generally held belief in our society, whether conscious or not, that learning requires teaching.

But notice that the insight is not that there is no such thing as teaching or that teaching is bad. It’s true, we probably don’t need nearly as much of it as we thought, but if I wanted to learn a specialized skill and I knew someone who could teach me it, then I’d be glad to have that option. Wouldn’t you? (Or would you continue to shun “teaching” and pick a different hobby?)

Of course, experience can be a “teacher” too, as in, “that experience taught me that…”. In that particular sense, teaching happens all the time. Either way, the word “teach” is, like any other English word, perfectly useful and can mean many different things. I give you permission to use it.

“Unschooling” vs. “Radical unschooling”

“Radical unschooling” is a useful term, in that it designates a specific flavor of unschooling. More than an educational philosophy, it describes a philosophy of parenting or even a philosophy of life. Among other things, radical unschoolers eschew the idea of parental authority. The fact that “school” is part of its title is a historical accident. Radical unschoolers see their philosophy of life as a natural extension of their educational philosophy (though, again, they may choose not to use the term “educational”).

“Unschooling” without the “radical” part is also a useful term. A broader group of people self-identify as unschoolers than as radical unschoolers. They represent a wider variety of parenting styles (including approaches to discipline). Moreover, the fact that “school” is in the title is very useful, as it designates an approach to education. It provides an answer to the question: what do you do for (or how do you approach the question of) education and school and stuff like that?

Some (notice I didn’t say “all”) radical unschoolers may take issue with the above distinction, perhaps even going so far as to say that someone who is not a radical unschooler is not a “true unschooler”. But language is more democratic than they realize. “Unschooling” can and does, for many people, mean the approach they take to education. It doesn’t necessarily denote their all-encompassing philosophy of life that trumps everything else. (That’s why adding “radical” was a useful thing to do.)

“Rules” vs. “Principles”

This, again, is a useful distinction. The idea here is that rules are situationally specific and extrinsically motivated. (“No hitting.”) Principles are broadly applicable and intrinsically motivated. (“Act lovingly.”) Read Sandra Dodd’s summary of the discourse among unschoolers on this point.

Now here’s my complaint. This distinction has become so overused that “We live by principles instead of rules” has itself become a rule! What was a helpful distinction has become ironclad dogma. It degenerates to: “We never use rules.” “Rules are bad.” “Rules are always bad.” “If it’s a rule, we don’t want it.” Thinking goes out the door.

Yes, please live a principled life. But what kind of principle is “rules are always bad”? Does that mean laws are always bad too? There’s really no need to paint with such broad strokes. You only end up painting yourself in a corner. There’s no need to make mental contortions like, “If we ever do anything that looks like a rule, we’ll be sure to call it something else.” Wouldn’t you rather be free to use whatever term you want? Access the inner rebel that led you to unschooling in the first place. Think and speak freely, and if some vocal unschoolers react in a knee-jerk fashion to your choice of words, call them on it. Tell them to follow their own principle and quit acting like it’s a rule.

Conclusion

Go beyond what words people are using and listen to what people are actually saying. Terminology is important, yes. If we don’t share a common language, then how can we understand each other? And how could a movement grow without a search-engine-friendly name (like “unschooling”)? But use words lightly. Don’t let them master you. Don’t let useful distinctions turn into dogma, helpful insights into ideology. Otherwise, we may as well stop talking to each other.

Nina JeckerByrne recently commented on another website about her experience with sending her children to a Sudbury school (in New York). With her permission, I’ve decided to quote her comment in its entirety (emphasis added):

As a culture we have a death-grip on our belief that kids must be taught x, y, and z or we’re all doomed. Those industrialists did a good job of selling their agenda to the masses! I am sure more and more people will decide to give up on compulsory education, and Sudbury and unschooling will eventually meet with less objection, we just have to be patient and let the outcomes speak for themselves. My oldest is 16, has been at the Hudson Valley Sudbury School for 7 years, and was unschooled previously. He’s never had to study or take tests. He decided he wanted to be a lifeguard for summer employment, took the course and passed all the tests easily! He did it all without reminders or help. He just recently got a 100 on his driver’s permit test after studying on his own for that. No one has ever “taught” him how to read or do arithmetic or how to study for a test, and he is competent in all those things, and is a whiz on computers – especially with Photoshop. All this without formal instruction – entirely by his own motivation and effort. He has demonstrated that he can learn whatever he wants to learn, whether it is on his own or by seeking assistance. We have been underestimating our children in this society for so long that we no longer trust in what is, in fact, natural – kids naturally want to learn and to challenge themselves, unless it has been trained out of them.

What could be more valuable than being able to learn whatever you need to learn whenever you need to learn it? That’s a skill worth taking into adulthood and doesn’t correspond to any particular subject that can be taught. If kids can develop their innate ability to learn and carry it into whatever area interests them, they’ll develop self-efficacy. In other words, they’ll have the general knowledge about themselves that “I can do it”, or “I can figure out what help I need to get it done”. How can you teach that? It has to be learned by experience.

Nina’s story is so typical of kids that are allowed to go all the way through a Sudbury school experience. The school that started it all, Sudbury Valley School, has published extensive information about their alumni. Two books in particular are worth reading if you’re at all concerned about what becomes of students who spend their childhood at a Sudbury school. See the “What becomes of students” page on the SVS website if you’re interested in reading these. One is called The Pursuit of Happiness: The Lives of Sudbury Valley Alumni (2005), and the other is Legacy of Trust: Life After the Sudbury Valley School Experience (1992). If you like quantitative data, you’ll like Pursuit of Happiness, but if you’d rather hear more from the alumni themselves (in the form of essays), read Legacy of Trust, even though it’s a bit older.

Last month, I got into a taxi cab after a whirlwind business trip. I was tired and ready to crash, er, sleep, on the airplane. I wasn’t feeling particularly outgoing. Even so, I engaged in some minimal small talk with the taxi driver. I saw a photo of a little girl on the dash. “Is that your daughter?” So it was. Shortly thereafter I had to explain that “What grade are your kids in?” is N/A for my family. “They go to a non-traditional school.” I would have been happy to leave it at that. But ’twas not meant to be.

Last month, I got into a taxi cab after a whirlwind business trip. I was tired and ready to crash, er, sleep, on the airplane. I wasn’t feeling particularly outgoing. Even so, I engaged in some minimal small talk with the taxi driver. I saw a photo of a little girl on the dash. “Is that your daughter?” So it was. Shortly thereafter I had to explain that “What grade are your kids in?” is N/A for my family. “They go to a non-traditional school.” I would have been happy to leave it at that. But ’twas not meant to be.

Before I knew it, I was expounding on the wonders of a Sudbury education, what a gift it is to children, how amazingly well-adjusted Sudbury school students are, how in touch graduates are with who they are and what they want, how they learn responsibility by being given responsibility, how they respect others and are themselves respected. At each stage, I expected him to say, “That sounds nice, but what about ____?” For example, when I told him that each student has a vote that’s equal to any staff member’s and that staff are voted in (and out)—when I told him that, like most people, he was astounded. But unlike most people, he didn’t get stuck there. He just wanted to hear more. So I kept going.

By the time we reached the airport, I was already flying high. How big a difference it makes when people respond with open minds! When sharing something you’re passionate about doesn’t turn into a big, adversarial debate! I don’t know what this man will do with the information. I don’t know if he’ll be pulling his daughter out of school anytime soon. But I definitely felt his sincere appreciation for all the new information I was telling him. “God bless you. You’ve taught me a big thing today.” And I in turn was very thankful for his expression of gratitude and the jolt of energy it gave me. Who would have thought a taxi ride could be so refreshing?