Hi everyone, I know I haven’t written any new posts here for a couple of years, but I’m going to leave this open just in case I get inspired to start writing again.

In the mean time, I started another blog which you might find interesting. It’s called Trust the Upward Spiral. Here are some of the articles so far:

- Mother your body—Man up your mind

- Making peace with structure

- Healing eyes

- Creativity song

- The structure of faith

I also welcome you to friend me on Facebook, where I’ve been more active lately. Or connect with me on Twitter. Thanks for reading.

It looks like you're new here. You may want to sign up for email alerts or subscribe to the "Lenz on Learning" RSS feed. Thanks for reading.

One of my favorite quotes is from Scottish mountaineer, W. H. Murray. I think it contains a lot of truth. “What am I committed to?” is one of the big questions I’ve been learning to face most days. I also find it pretty difficult to answer. But that’s not the hardest part. Once I’ve defined what I’m committed to, it’s then a matter of really committing to it, come hell or high water. That kind of commitment has real legs:

Until one is committed, there is hesitancy, the chance to draw back, always ineffectiveness. Concerning all acts of initiative (and creation), there is one elementary truth the ignorance of which kills countless ideas and splendid plans: that the moment one definitely commits oneself, then Providence moves too. A whole stream of events issues from the decision, raising in one’s favor all manner of unforeseen incidents, meetings and material assistance, which no man could have dreamt would have come his way.

When you burn your bridges and decide not to look back, new vistas of possibility open up. All your attention is focused on forward movement and finding ways to make things happen. Retreat isn’t on your radar. Only then do things start happening; the universe suddenly seems to join your team.

What are you committed to? Are you really committed to it?

Whatever style of education your kids are receiving right now, whether it’s homeschooling, unschooling, democratic schooling, private school, public school—honestly ask yourself this question: Are they happy? Are they thriving and growing and loving life? If the answer is yes, don’t change a thing.

If you feel compelled to change something for some other reason, such as that they aren’t learning X, Y, or Z, my advice to you is this: open your eyes and appreciate what you’ve got. Your kids are happy and thriving and growing! Why would you want to mess with that?

We have such a preoccupation in our culture with the content of what kids learn. We get constantly distracted from what’s in front of our faces. The key to making good decisions for your kids—and helping them make good decisions—is to pay attention to what’s happening now. Don’t get caught up with the future or the past. Are they happy where they’re at? Then let them be.

What are the prime conditions for learning? Witnessing my own kids, I can tell you that they grow and learn at an amazing rate whenever it’s obvious that they really love life. It’s when they’re experiencing sustained difficulty or discontentment that we start to question the way we’re doing things.

Some kids are happy, but their parents aren’t happy for them. What’s wrong with this picture? Who has a problem—the kids or the parents?

Jerry Mintz, founder of AERO, recently updated his helpful article: Ten Signs that You Need to Find a Different Kind of Education for Your Child.

Here’s a quick summary. First, the ten signs that your child may need a different kind of education:

- Declarations that “I hate school.”

- Difficulty interacting with people of different ages

- Unhealthy fixation on fashion

- Tiredness and crankiness

- Complaints about conflicts and unfairness

- Lost interest in creative expression

- Apathy toward subjects that were once exciting

- Procrastination

- Lack of excitement

- School recommendations for ADHD drugs

Mintz then goes on to cite a number of educational alternatives. Many parents aren’t aware of what might be available to them:

- Publicly-funded charter schools

- Montessori schools

- Waldorf schools

- Sudbury schools, and other democratic schools or “free schools”

- Public school alternatives:

- Public Choice/Schools within schools

- Public At-Risk

- Homeschooling:

- “School at home”

- Unschooling

For more details about the signs and the alternatives, see the original article: Ten Signs that You Need to Find a Different Kind of Education for Your Child.

Grading as an educational methodology does a great job at helping you learn, especially went implemented from an early age. Below are five things you are likely to learn.

1. An inflated sense of self

Whether you get A’s, F’s, or anything in between, you learn that life is largely about what people think of you. If you are a star student, then you are placed on a pedestal, groomed and adored like a well-bred animal, and showered with awards and accolades. You learn that you are the one that is “most likely to succeed.” A friend recently reflected on how difficult college was. His previous schooling had taught him that he could do no wrong, that everything he touched would turn to gold. When he failed his first test, it burst his inflated sense of self and sent him reeling into depression.

If you struggle to get even decent grades, then you get your own set of labels. You learn that you are learning-disabled—that you are unable to learn. You are defective. You require special classes, medication, and tutoring. You are the most likely to fail in life.

Constant evaluation makes life all about you and what people think of you. You either please them or disappoint them. Either way, all eyes are on you.

2. An abdication of responsibility

Grading encourages you to abdicate all responsibility for evaluating your own learning. That’s somebody else’s job. Other people know better about not only what you should be learning but how well you are learning it. This is their game, and it’s your job to play it. Why you would want to learn something, what you would apply it to, what meaning or importance it has for you, what enjoyment you get from it—these are completely irrelevant to your grade. So why even pay attention to these considerations? They are a waste of time. They’re not going to help you pass that next test.

3. An extrinsic orientation

Grading takes your attention off what is being learned and whatever intrinsic value it might have for you. Whatever you’re learning is merely a means to an end. You learn things so that—so that you can get a good grade, so that you can go to college, so that you can get that scholarship, so that your parents will be proud of you. You learn to de-value enjoyment and engagement for the sake of enjoyment and engagement. Constant grading is a great way to prepare you to be an adult in a materialistic society in which you are always working for tomorrow, because what you have now is never enough.

4. A competitive mindset

You learn that your classmates are your competitors. Only one person can be valedictorian. Not everyone can enroll in the gifted class. You quickly learn your station in the caste system, whether you are more of a winner or a loser. Everyone else is a threat. You happen to share a classroom with them, but you soon learn that you are on your own.

5. A judgmental attitude

If all goes well, you adopt grading’s value system as your own. You learn to put labels on other people. You learn to size them up at a glance, to quickly categorize them and judge them and assume you know what kind of person they are (bright, lazy, dumb, diligent, unmotivated, etc.).

Conclusion

Don’t let anyone tell you that grading doesn’t work. You can learn a lot from grades.

Have you ever wished you could know what a baby was thinking? After they’ve begun to develop language, we get to peek inside their toddler minds. As children grow, they make continual refinements to their model of the world. Along the way, they come up with some pretty funny misconceptions. I think this is part of the process of learning in general. Misconceptions are essential stepping stones to learning.

Last year is when I dropped the bombshell. I told Lucas (3) that Sid from Ice Age was not actually real. I then proceeded—cold-hearted father that I am—to show him an interview with John Leguizamo on YouTube. Lucas had a sort of stunned look on his face as his brain scrambled to make sense of what he was witnessing. “That’s clearly Sid’s voice…but that’s not Sid…” It took him a few minutes of follow-up questions and explanations before he finally accepted that Sid was a fictional character. I felt mean, but I also liked that he had this newfound realization. The next thing he asked, looking to me for reassurance, was “But Diego—he’s real, right?” I think I may have (or at least should have) waited until the next day to introduce him to Denis Leary. You can only take so much world-shaking in a day.

Last year is when I dropped the bombshell. I told Lucas (3) that Sid from Ice Age was not actually real. I then proceeded—cold-hearted father that I am—to show him an interview with John Leguizamo on YouTube. Lucas had a sort of stunned look on his face as his brain scrambled to make sense of what he was witnessing. “That’s clearly Sid’s voice…but that’s not Sid…” It took him a few minutes of follow-up questions and explanations before he finally accepted that Sid was a fictional character. I felt mean, but I also liked that he had this newfound realization. The next thing he asked, looking to me for reassurance, was “But Diego—he’s real, right?” I think I may have (or at least should have) waited until the next day to introduce him to Denis Leary. You can only take so much world-shaking in a day.

A misconception I had when growing up had to do with chewing gum in bed. My mom told me that I mustn’t go to bed with gum in my mouth, because it might end up in my hair. I always wondered at this mysterious process—how the gum would work its way deeper into my mouth, up through my head, out through my skull, and into my hair. In any case, I didn’t want to test it out.

And then there are the verbal idioms we pick up without having any idea what their origin is. This is fine except when we don’t get it quite right. Oftentimes, these don’t surface until we write them on paper. My mom used the phrase “for all intents and purposes” quite a bit. So did I. Except that I always said, “for all intensive purposes.” It pretty much sounds the same when you say it out loud. The fun thing with Google is that you can find other people making the same mistake you made. I didn’t realize my mistake until college, but Google reassures me that there are about 406,000 other people making the same mistake, so I don’t feel so dumb.

Misconceptions are a part of life and learning. They can be funny sometimes. Do you have any favorite misconceptions or delusions you’ve labored under for some part of your life? Or stories about how your kids have made humorous conclusions about what’s true or how things work?

Do you ever wonder why kids like to be read the same book over and over again? Or play the same game, or watch the same movie, over and over again? I wonder about that. One guess I have is that they want to master the content. Another is that, when you’re young, everything is wonderful, and few things get boring. When you find something you enjoy, you want to keep enjoying it. It takes a while before it loses its novelty.

My 3-year-old son Lucas has a favorite book that we read almost every night: The Very Bumpy Bus Ride. He also likes it when Sammy (9) reads it to him. But one night—I can’t remember how this started—we started being silly about how we read the words. Oh yes, I remember that, after Sammy had read it to him for several nights, when I came back, he thought it was funny how I said “Mrs. Fitzwizzle.” All I had to do was say that once and he would crack up. So I tried saying it several times in a row, and he cracked up even more. I can still get him to laugh, just by saying that name.

My 3-year-old son Lucas has a favorite book that we read almost every night: The Very Bumpy Bus Ride. He also likes it when Sammy (9) reads it to him. But one night—I can’t remember how this started—we started being silly about how we read the words. Oh yes, I remember that, after Sammy had read it to him for several nights, when I came back, he thought it was funny how I said “Mrs. Fitzwizzle.” All I had to do was say that once and he would crack up. So I tried saying it several times in a row, and he cracked up even more. I can still get him to laugh, just by saying that name.

From there we started messing with the other words. Doing baby talk or talking like a ventriloquist or flipping the sounds around, as in “The Bery Vumpy Rus Bide.” (This spoonerism approach in particular cracks Sammy up.) Now Lucas contributes to the word massacre by mixing his sounds around and being silly about it. He practically has the whole book memorized, so he’s getting pretty good at saying the sentences while flipping the sounds around, saying nonsense words that rhyme with the originals.

In the past, I might have had some concerns about this game, fearing that he’s learning the words the wrong way. But now I laugh at the thought. He clearly knows the words, and adding this layer of processing complexity (starting with the original and coming up with a non-sensical rhyming word) does two positive things, as far as I can tell. It reinforces his knowledge of the words by engaging with them in new ways. And it makes him want to continue by keeping things fresh and fun.

Another thing I like about reading the same book over and over again is that kids start making some pretty astute observations. I imagine that the earliest tendency of most kids, when being read to, is to associate the words they hear with the pictures they see. The letter symbols, to them, are just extra clutter on the page. This was also evident with Lucas when he would ask me to “read” particular things he saw in the picture. And I’d tell him, “It doesn’t say anything about that. The only words are these ones down here.” Once he started to realize that, he made the observation. “Daddy, isn’t it funny that on the big-picture pages, there aren’t very many words, but there are lots of words on the small-picture pages?” That’s when I taught him how to spell “counter-intuitive.” 😉

If you want to hear more stories about the diverse ways in which kids engage words and eventually learn to read, I highly recommend Peter Gray’s recent article about this topic: “Children Teach Themselves to Read” .

“What about socialization?”

Homeschooling families are all too familiar with this question. I remember growing up as a homeschooler and hearing people express their grave concerns about how we would ever function in society. “They really should be in school—to be socialized.” And then as an adult, unschooling our own children, I remember hearing this question and being defensive about it. For a while, I’d point to all the social activities the kids were involved in, like play dates and church activities and field trips. But then as I continued to read and reflect more about the social institution of traditional schooling, I stopped being defensive. It suddenly became easy to answer the question.

Yes, what about socialization? What kind of socialization do I want for my kids? Do I want them to be imprisoned in classrooms segregated by age? Do I want their lives to be driven by bells? Do I want them to grow up in a social atmosphere in which kids are pitted against adults—a breeding ground for resentment, suspicion, and bad attitudes on either side? No, I’ll spare my kids that sort of “socialization,” thank you very much. It’s too disconnected from the real world. Or maybe it’s all too connected—connected to the dreary lives that people willingly choose, in jobs they hate, serving people they despise. Do I want my kids to learn that it has to be that way? No, thank you. You can keep your “socialization.”

That was my attitude. It was a bit harsh and unrefined and certainly not the whole truth, although I still think there is truth to it. In recent years, we discovered Sudbury schooling and our minds opened to further possibilities and definitions for “socialization.” Merriam-Webster defines “socialize” as:

to make social; especially : to fit or train for a social environment

When we learned about the social environment of Sudbury schools, loosely characterized as “unschooling schools,” we started to see some value over and above what unschooling had to offer. And it almost entirely had to do with the social environment. I still didn’t like the term “socialization,” because it brought up for me what most people are referring to—school-ization. But now we were thinking about it in a new way. I’ll get to that in a minute, but first let’s go back to some basics.

Attachment is foundational

Growing up is about becoming independent. When we’re born, we’re totally dependent on our parents, especially our mothers. We’re not only physically dependent on them, but emotionally too. The quality of our attachment to our parents is crucially important for establishing security and a sense of well-being in life. That sense of security leads into self-confidence later in life. Over and over again, attachment parenting has shown that—far from kids becoming overly dependent on their parents, they establish such a sense of security that, when they get older, they feel emboldened to take things on by themselves. They somehow internalize the sense of security they got from the close bonds they had with their parents so that even when they ostensibly break those bonds, they continue to carry that sense of security with them into adulthood.

And I honestly think that will be true regardless of what schooling environment kids find themselves in (traditional, unschooling, or otherwise). By the time they go to school, it’s relatively late in life. They’ve had a chance to either develop strong bonds with their parents and that attendant sense of security, or not. (Maybe I should spend more energy evangelizing attachment parenting rather than educational alternatives, but I digress…) Even so, people are resilient, amazing creatures. We’re always adapting to our environment, learning new things, refining our model of the world, and growing. The longer I’ve reflected on this, the more laid back I’ve gotten about schooling choices. “Huh?” you may ask. “What about all the rhetoric on this blog?” Well, it’s true, I do want to jar people into thinking about this stuff. It is important. But ultimately, except in the worst of situations, kids are not going to be destroyed. There are plenty of happy kids in public schools. They’re learning to cope and make sense of their world just as much as anyone else.

Parents have choices

So… where am I going with all this? It’s here: It was from a place of freedom and choice that we decided to send our kids to a Sudbury school. We started off with the assumption that, no matter what schooling environment we put our kids in, they would not self-destruct. We trusted them to not do that. Having achieved that sense of clearing, we then felt the freedom to let go of our dyed-in-the-wool unschooling philosophy just enough to allow for a different kind of experience—at least to try it out. And we haven’t been disappointed. Nor have the kids. Otherwise, they wouldn’t still be attending. (And who knows, they may still decide to go down a different path one of these years.)

Trust is contextual

Is sending your kids to a Sudbury school an indication that you don’t trust them to thrive at home? Have you then failed at trusting your kids? This is a trap. I could just as easily apply that logic to traditional schooling. Is pulling your kids out of public school an indication that you don’t trust them to thrive at school? The point is that trust is contextual. Trust as a value in and of itself is a bit misguided. We need to be specific about who and what we’re trusting. Otherwise, we can hoodwink ourselves into thinking that making any choice for change indicates we’ve somehow failed at “trusting.” Can you think of any examples of people or situations you do not trust? Or that you should not trust? Does that mean you’re not good at trusting? More to the point, can you think of two good, trustworthy things and yet choose one over the other?

For my family, unschooling and Sudbury schooling were those two good things. We’d be happy doing either. But we saw even more value in Sudbury than in unschooling.

The positive side of socialization

In particular, we saw that, by separating from their parents for a period of time each day, our kids would learn a measure of independence they would not gain—or not gain as effectively—without doing so. This was not easy. We had to let go of being aware of what they were doing all the time. We enjoyed the privilege that unschooling parents have: experiencing and sharing in practically all their growth experiences. That was hard to let go of. But we could see—and were convinced by everything we learned from others who had gone before us—that there was gold in them thar hills.

To be around your parents constantly, even as you grow beyond 4, 6, 10, 13 years old is to miss out on the opportunity to experience early on what it’s like to participate in a larger community as an individual without the safety net of having your parents nearby. Parents, regardless of parenting style, have an immense power over their kids. We see many parents abuse this power. We also see parents take this power very seriously, doing everything they can to ensure that their influence on their kids will be a good one. Yet if your parents are never far from your side, you are missing out on the opportunity—I know this is a statement of the obvious—to experience yourself outside that context.

We were impressed by the kids we saw in videos like Voices from the New American Schoolhouse. We were impressed by how articulate and thoughtful these kids were, by how considerate they were of other people in their environment, and by how much they valued respect and responsibility. And, yes, we made value judgments. We were making judgments about what we valued for our kids; among those values was the desire for our kids to have the experience of making their own value judgments and decisions about what to do with their time in contexts unmonitored by their parents. We saw that by sending our kids to a Sudbury school, they would be free—even more free than as unschoolers—to grow into the contours of their unique potential.

And of course, it’s not just separation from parents that is valuable. It’s the participation in a wider community—larger than one’s own family, sharing space and resources, learning to respect other people, learning responsibility, learning how one’s own actions affect others, whether positively or negatively. It’s about broadening your social awareness and deepening your social skills by participating in a wider community.

We also saw that we could do this without giving up family togetherness and cohesion. We still have mornings and afternoons and weekends to do stuff together, to enjoy each other’s presence, to love each other and grow closer together. And we are rejuvenated when we reunite. It’s a win/win solution that works well for our family.

Does Sudbury schooling then differ in philosophy from unschooling? There’s no doubt about it. Are there commonalities? Yes, definitely. Are you as parents free to make choices in what to suggest for your kids? This article is an attempt to consciously and honestly influence you to answer “yes.” But that too is your choice.

I recently signed up for an amazing service called Peer Success Circles. It has absolutely transformed the way I go about my work. With a daily accountability partner, I’ve been much more effective and efficient at getting things done and moving forward on my goals. I’m now in my fifth week of this program, and I’m still loving it. It has become a new way of life. I should have started this long ago.

But one thing I’m learning this week is that I still need to take time for reflection. (Thankfully, the questions in this program naturally drive you into doing that too.) In the past, I actually reflected—or daydreamed—too much. I’ve now become much more action-oriented. Each day, I create a plan of attack, complete with a specific schedule of how I’m hoping to spend my time. And I track how I do—how closely I stick to the schedule, taking note of where I deviated. I’m developing new habits. Rather than habitually looking back at where I just was, I move forward. Reviewing how I did at the end of each day does wonders for my self-awareness, for staying on track, and for finding ways of doing better tomorrow.

This process works very well for my work. Time is the raw material, my schedule is the function, and productivity is the result. A simple equation. But when it comes to family time–time spent in moment-to-moment interaction with my wife and kids, it can’t be so easily structured. And perhaps it shouldn’t be either. We have been scheduling PlayTime, and I think that’s a good way to ensure that we keep it up. But for most activities, in order to be realistic, I have to leave family time pretty open-ended. And I’m okay with that. But I find myself in the position of having this great, new, exciting, effective process for making me more effective at work (basically, a daily schedule) and no corresponding great, new, exciting, effective process for family life.

Don’t get me wrong. It’s mainly just the scheduling aspect that doesn’t work for family time. The rest of the Peer Success Circles process is still very helpful. Setting goals, articulating what I’m committed to, what’s the driving force behind my actions, reflecting on how I did each day, etc.—these are all amazingly effective for making a positive impact on my family life too.

So what am I complaining about? I don’t know. Maybe the “problem” is disappearing before my eyes. It’s not as if I’ve always been a compulsive, schedule-oriented type. I’ve always thought of myself as more of a “dreamer,” favoring unstructured time. (Of course, that appears to be changing now.) So I get to still favor unstructured time when it’s with my family. It is nice to come to the end of the work day and let go of my schedule for a little while.

But I still face challenges, and I think it comes down to difficulty with being in the present moment, wherever I am. What is “time” anyway? I’ve made it this thing that I manage. And that’s working pretty well for me. But it’s really just a concept, not real in and of itself. Maybe I need to find a way to let go of time when I’m with my family. I’ve recently heard that “time is an emotion.” That’s an interesting concept, even if I don’t fully understand what it means yet. But I think I’ll reflect on this some more—you know, do some daydreaming about it. Yes, I think I’ll daydream about being engaged in the present moment. (That was a joke—and it would be funny if it weren’t so true.)

My first exercise will be to take a shower tomorrow morning and engage fully in what I’m doing. When I’m washing my face, I’ll think about nothing but washing my face. When I’m rinsing my hair, I’ll think about nothing but rinsing my hair. Once I’ve started to make some progress on this, I’ll step it up and bring the intention over to my family time, at the end of the work day. (PlayTime is already designed for this. Actually, it’s a sort of present-moment/daydream hybrid…which perhaps is a good characterization of play itself…). The correct word seems to be “mindfulness” (but I wonder if that’s a misnomer…).

I’ll be sure to schedule a follow-up post on this. All in good time.

As a parent, I have my off days and my on days. This is one of the off days. I don’t feel like writing, much less writing about parenting. But maybe this is an opportunity to push through the resistance and learn something new.

I have been grumpy this week. There are several contributing circumstances—crummy weather, sickness, and work disruptions. I’ve been up at night with my 3-year-old, so my sleep hasn’t been up to par. It’s easy to see the reasons, and it’s comforting to know that these too will pass.

As a matter of fact, just as I wrote that, the clouds parted and sun shone through my skylight right onto me, if only for a minute. I’m grateful to be alive, even if I haven’t been acting like it.

Bedtime had been smooth sailing lately—until this week. What do you call that capacity—patience? It’s the capacity for handling loud noises and feet-dragging kids. It’s the capacity for looking beyond yourself and seeing what is going on in other people’s lives. Compassion? When I don’t have it, or when it’s in diminishing supply, I feel like I’m missing out on real opportunities. And I feel like I’m better off staying at home where I won’t inadvertently hurt anyone.

Last night, while I was brushing my teeth, the cat jumped onto my back, sinking in its claws. Hopefully my kids didn’t hear me shout it. “Stupid #@*&#$ cat!” Poor thing. I actually really love our cats. Earlier this morning, I had a nice snuggle session with Brownie. It’s just that Boots picked the wrong time to do that. At least my lash-out was only verbal. And he didn’t appear to be offended.

A little bit of reflection can be therapeutic. At least that’s the idea here. And it’s good to laugh at oneself every once in a while. The clouds are parting again. I’m going to sit and bask a little.

When we were transitioning from unschooling to enrolling our kids at a Sudbury school, we saw it as a trade-off. We were losing some things and gaining some other things. It’s not that we decided that unschooling was bad or wrong. Instead, we were attracted to the benefits we thought our kids would get from the change. In practice, although we encouraged it, it was still up to them. Our daughter Morgan immediately loved it and never looked back. Our oldest son Sammy visited for a couple of weeks and then decided he wanted to stay at home instead. So we let him do that. There was no coercion involved; it truly was up to him. A year and a half later, he decided on his own that he wanted to do it after all, and now he looks forward to school every day too.

We love unschooling, but we love Sudbury schooling (specifically The Trillium School) even more.

There are definitely benefits that are unique to unschooling, as opposed to Sudbury schooling. When compared to Sudbury schooling, unschooling affords:

- More family scheduling freedom

- More time with one or both parents

Many unschooling parents won’t be willing to let go of these benefits of unschooling. And I totally respect that choice. My point in “Unschooling vs. Sudbury schooling” was to compare and contrast two wonderful alternatives, not necessarily pit them against each other.

But there was one phrase in my last post that hit a nerve, despite my intention to write objectively. Regarding what Sudbury schooling offers in differentiation to unschooling: “For a significant period of time each day…[kids] pursue their interests in a context that’s free from any form of (subtle or overt) parental influence.” I think it’s possible to read that as a factual statement without the connotation that being with parents is bad. Consider this: I wrote it, and I think parental influence is a good thing. Let me repeat: yes, I want to influence my kids—by my example and whatever wisdom I can share with them while they’re living with me. (No, I don’t want to control their choices. I trust that they are learning to make authentic choices on their own, that they will learn what they need to learn, and that they’ll grow into wonderful adult human beings.) By the way, please substitute a different word for “influence” if it inherently brings up negative connotations.

Nevertheless, it did hit a nerve. In “The Dark Side of Influence,” Wendy Priesnitz criticizes Sudbury schools as being based on “faux-democracy” and “substituting adult’s choices for children’s choices.”

The idea is noble: to help the kids make a commitment, to foster cooperation and relationships, and to help them learn about consequences. But, in short, it’s about adults enforcing something on kids because it’s assumed they won’t learn the stuff on their own, that they don’t know what’s in their own best interest, that we have to make them do stuff “for their own good.â€

This is a mischaracterization of Sudbury schooling. They won’t learn what stuff on their own? Adults enforce what exactly? What are kids made to do “for their own good”? The only evidence she cites is the attendance policy. The one concrete thing that students are supposedly “coerced” to do is attend school. Yet here is the extent of the “coercion”: If you want to be here, you have to be here. If you stop attending, you may lose the privilege of attending. We ask you to be here for, say, 5 hours per day. Do you want to make that commitment? (It’s up to you.)

There are good reasons for requiring this commitment, not the least of which is cohesiveness and continuity of the community. Regardless of the reasons, this is definitely an adjustment for families that aren’t used to it. It’s an adjustment for both the parents and the kids. But they are entirely free to opt out (as my son did). Oftentimes, it’s the kids (especially when they’re older) that find out about their local Sudbury school and convince their parents to make the commitment that they’re so ready to make.

Note: In practice, attendance, while taken seriously, is flexible, provided that everyone is communicating. Policies will vary from school to school, but one family at Trillium is on a two-week vacation right now. They let the school know, and everyone was totally cool with it.

Ultimately, I get the feeling from Wendy that she thinks that Sudbury schooling represents a fake form of trust. But which requires greater trust? Keeping your kids in your care all day, where you know what they’re doing and who they’re with at all times? Or sending them to a place where they are afforded the same sort of freedom but without you there to watch? Whether or not this is valuable is another question. We’re not having a “parental trust contest,” I hope. I’d rather focus on what’s best for particular families and particular kids. Sudbury has a lot to offer that unschooling doesn’t, and vice versa.

So let me try again, using different words:

- Fact: Sudbury students are separated from their parents for a significant period of time each school day.

- Fact: Sudbury schools tend to be significantly larger and more diverse than individual families. As such, community agreements are made using a formal democratic process.

Please consider that, by pointing out these rather obvious distinctions, I am not attacking unschooling. What I’m trying to do is this: help parents think through what their options are, comparing and contrasting different aspects of each approach.

And I still haven’t even gotten to the benefits that I see as unique to Sudbury schooling. In other words, why might an unschooling family consider Sudbury schooling to be a desirable choice (as we did)? That will have to come in another post.

“It’s an ‘unschooling school,'” is what someone told me when I first heard about Clearwater School, and Sudbury schools in general. How appropriate is that characterization?

Similarities

Both unschooling and Sudbury schooling value the concept of self-directed education. Proponents of both share common insights and make some of the same challenges to traditional schooling:

- People are born learners. Children are trusted to have the desire and ability to engage in—and learn how to operate effectively in—their world.

- Coercion creates resistance. Forcing people to learn something tends to spoil it for them. It becomes something they have to do, not something they might choose to be interested in. Force takes away that possibility of choosing. Done systematically, you can spoil a whole range of subjects. Consequently, force in the form of required curricula is eschewed.

- Conversely, people learn best when they’re interested in what they’re learning. A high value is placed on what children are interested in. Supportive energy is directed to helping them succeed in the goals they choose for themselves.

- People are different. They have different interests, aspirations, and passions. Consequently, children aren’t expected to learn the same things as everyone else.

- People grow at different paces. Consequently, children aren’t expected to, for example, learn to read at a specific, pre-determined age.

Differences

Despite all the similarities, I can think of two ways in which Sudbury schooling differs fundamentally from unschooling:

- Kids at a Sudbury school are regularly separated from their parents for a significant period of time each day. They pursue their interests in a context that’s free from any form of (subtle or overt) parental influence.

- The social structure of a school is necessarily different than the social structure of a family. Sudbury schools are run democratically, where School Meeting is the single authority within the school.

The aspects of separation from parents and formalized democratic process make Sudbury schooling look quite different from unschooling, as it turns out.

I think I’ll explore what’s significant about these differences in a future article.

For me, the most important thing about PlayTime is the guaranteed one-on-one interaction I get with each of my kids. Most of the time, we try to stay in the structure of child-led play, but sometimes we’ll deviate a bit. Last week, my daughter Morgan and I went for a walk on the beach. It extended for well beyond the designated time, but since we weren’t engaging in full-on play (which tends to be exhausting for me), I was totally happy with that.

Yesterday was another beautiful day. I went on a run and stopped by at our beach to enjoy the sun. After I got back, it was PlayTime with Morgan again. She said she wanted to go to the beach again, but she ended up getting upset about not finding the clothes that she wanted to wear. When it became clear that she wasn’t going to budge, I suggested that we just do a regular PlayTime at home. But no, she still wanted to go to the beach. I asked her to “climb out of your hole”—a phrase that my wife recently started using with me when I’m in a bad mood, but that didn’t help either.

Then I noticed her American Girl doll and said, “Shall we play with dolls at home instead?” And just like that, she jumped up and said, “Okay!” and we were off. It turns out that Samantha and Kit are actually long lost sisters, with amnesiac parents named Paul and Polly, both of whom faint a lot. Also, Samantha loves horses but has never had one of her own. Imagine how excited I was—I mean she was—when she got a new horse for her birthday. Polly taught her all about how to groom the horse, brush its hair, curl its mane and tail, and even fix up a broken leg. Polly knows her stuff; she could barely get it all out when talking a mile-a-minute. The rocking horse still has its paper cast on this morning, but it should be able to come off soon.

That’s why I like PlayTime. Even in the face of a near melt-down, playing dolls with your Daddy can have an instantly positive impact on your emotional state.

Chip responded to my recent post on how Sudbury students learn self-discipline. To do his questions justice, I’m responding with another full post.

I quickly point out that I know little about the Sudbury approach so please forgive me for feeling like your answer is incomplete.

I think you’re right. There’s more that should be said about this.

“Sudbury students, by necessity, learn self-regulation, because no one else is there to regulate them…â€

That’s it? Taken out of context, that sounds like great potential for chaos. If there is no one there to regulate them, is there someone there to teach them how to regulate themselves? Does anyone there give them guidance? Kids don’t often have the same value system.

Each school has an implicit shared value system as reflected by their community agreements. All school members are held accountable to keeping those agreements. The Judicial Committee (JC) is essential in this regard. It provides a structure for the school to compassionately address complaints one member may have against another. The reality is that chaos does not reign at Sudbury schools. Stated more positively, the reality is that Sudbury schools are phenomenal examples of people being civil and respectful to each other. I think one of the key reasons for this is that there’s no one to rebel against. There’s no “us vs. them” mentality. There’s only “us.”

Chaos sometimes erupts in traditional schools because of an underlying pent-up urge to break out of all the externally imposed controls. When there are so many people (kids) controlled by so few (adults), there’s an imbalance in the system. Remove that imbalance and there’s nothing to drive an eruption, or to cause chaos to ensue. To assume otherwise is to assume that kids are chaotic by nature and that, if kept unchecked, kids will—I don’t know—self-destruct? Proponents of the Sudbury approach don’t share that assumption. And many, many years of experience haven’t given them any reason to think otherwise.

I’ve always felt that teaching kids self-discipline and respect for others should begin at home and be supplemented by the school. The two efforts should be complementary.

I agree that respect is learned (or not) both at home and at school. But the question should be: How is respect for others best learned? Should it be taught from without? Modeled by example? Coerced by threat of punishment? If a child acts “respectful” simply in order to avoid punishment, how genuine is that respect? Do we care if it’s genuine? Or is the respect afforded someone potentially related to the respect they will in turn afford others?

In this case, if the effort at home is lacking, it sounds like there isn’t a back-up plan at school.

On the contrary, respect for others is supremely valued by and foundational to the Sudbury school model. Kids find that they are respected as first-class people at school, even if they are used to being treated as second-class citizens elsewhere, whether at home or at their previous school. Once this realization sinks in, a wonderful thing happens. They stop fighting against the world. They start to lay down the defenses they’ve built up over the years. And they find a place from which to reach out to others in a loving way. Respect for others as human beings, regardless of differences in age or otherwise, is foundational. But it’s only the beginning.

Here’s a compelling vision. Wouldn’t it be great if we no longer had to ask the question, “How do we teach kids respect?” The Sudbury approach and others like it envision a world in which respect is part of the air kids breathe.

PlayTime is still a hit with the kids. I’m doing it twice a week with them on a rotating basis, for 30 minutes. It seems stingy when I think about it. That amounts to less than 30 minutes of play per child per week! But then I reassure myself that this isn’t the only time I’m playing or interacting with them. It’s just a particularly focused time of doing so. And I have to be honest. It hasn’t gotten much easier. It’s been challenging in two primary ways.

First, it’s challenging for me to focus on and visualize the scenarios they create. I have to listen and concentrate. And even though it’s only 30 minutes, I still find myself losing focus and asking, “Can you say that again?” I want to be clear on what it is I’m supposed to be doing. It’s better to fall slightly behind and then catch up quickly than to fall way behind, reveal it obviously by saying something dumb, and then witness that look of betrayal and disappointment. “Where have you been, Daddy?” But I’m slowly getting better. And I have hope that it will get easier. I haven’t reached that plateau where I’ve gotten caught up effortlessly in the play. There have been moments, but they’ve been isolated and short-lived.

I wonder if 30 minutes isn’t long enough for me to get past the hump of inertia? Maybe I need to expand the time a bit. This might help me let go of any clock-watching tendencies and lose myself in the play. Yes, I wonder if PlayTime just needs some tweaks.

If the kids love it so much, why would I want to change it? Well, I definitely take comfort in the fact that they love it regardless. Even if it never gets easier for me, that alone makes it well worth the effort. But making it more engaging for me, I think, would also increase the quality of the experience for both of us. And if my first tweak is to extend the session by 10 minutes, then I’m sure they’ll have no problem with that. It does always seem to end too quickly for them.

The second aspect that’s challenging is related to the first. Not only do I have trouble getting the play going, but sometimes the kids do too. At first, I thought this was just a matter of age. Sammy (9) had no problem at all getting started. All I had to do was keep up. He didn’t need any guidance, just supportive energy. My first PlayTime experience with Morgan (6) was a bit slower-paced, and it took her a while to get started, but soon she was off to the races too. With Lucas (3), I had to be more of a leader and be creative.

But since those first experiences, each of my kids have had their off-days. Sometimes it’s indecision about how to use the time. Other times it’s just a matter of not being inspired. So this is another reason I want to get better at it. When they’re not feeling particularly creative, I can contribute more and get the juices flowing.

Last night, I did PlayTime with Lucas. It took a little while to ramp up, but gradually he got more and more into the fantasy. He loves to shrink himself and go in tiny cracks in the floor or walls and then emerge out from some other surface. He’s definitely getting better at PlayTime. If he can do it, so can I. Right? Starting today, PlayTime will be 40 minutes long.

Chip recently asked, “How does the Sudbury model teach self-discipline?” This post is my attempt to address that question.

What is self-discipline? Merriam-Webster defines it as “correction or regulation of oneself for the sake of improvement.” How does one learn to regulate oneself? I’m in my 30s, and I’m still trying to figure out the answer to that question. I run my own business from home, and I’d be lying if I told you it hasn’t been a challenge figuring out how to consistently correct and regulate my own behavior. The Internet is a carrier of so many distractions, and my job involves being on the computer for most of the day. It does take real discipline—and the development of new habits—to resist those distractions and make myself focus on what it is I want to be accomplishing.

One of the chief things I’ve learned is that I need help from other people. I need a support network. In fact, I recently discovered that daily accountability is what really works for me. I have a call with an accountability partner every morning to review yesterday’s wins and challenges and to communicate my goals for today. This has been immensely powerful for me. Just that little bit of support has made it much easier to discipline myself and relax into the schedule I’ve laid out for myself on any given day.

I thrive on structure, but I don’t have a boss telling me what to do and when to do it. Instead, I’ve had to create my own structures, by seeking out help from other people. That alone has been immensely empowering—knowing that I can evaluate my own weaknesses and accordingly seek out the help I need from others. I’ve learned to regulate myself using whatever means I can.

Faced with gobs of time by myself, I am forced to consider what is important to me. If I care about something enough, I will figure out what I need to do to make it happen. I’ve gone through periods of discontent and boredom, passing the time, trying to figure out what I want and what works for me. At various times I’ve been tempted to go back to a “normal” job, where someone is there to tell me what to do all the time. But then I realize the deception. In my line of work (and in most people’s these days), it’s never that simple. You still have to figure out how to manage your time, boss or no boss. And I remember all the freedoms I’d be giving up if I were to do that. So I re-focus and find the resources to make it work.

This is similar to the plight of a Sudbury school student—with the major difference being that Sudbury students already dwell in a richly supportive and stimulating community of people. (I’ve already confessed my envy over that.) But the gobs-of-time component is the same. Time is the clay of life, and it’s their responsibility to figure out what they want to sculpt. Structures and support are available, but the onus is on them to request help in creating them. Sudbury students learn that if they want something to happen, they’re the ones who are going to have to make it happen.

Sudbury students, by necessity, learn self-regulation, because no one else is there to regulate them—except insofar as they are held accountable to keeping community agreements, i.e. rules. The Judicial Committee (JC) is the school structure to ensure that all people (staff or students) are held accountable for keeping community agreements. (You can read more about JC here.)

In a traditional school, discipline is externally imposed. Students learn to do as they are told. They are taken to account for deviating from their prescribed activity. Figuring out what to do with their time is not something that students in a traditional school have to worry about (at least during school hours). These decisions are made for them anew every day. Of course, there are certain freedoms, and learning definitely takes place. Students learn how to cope with externally imposed schedules, and they learn to make choices about what attitudes they want to bring to school. But it’s a narrow form of freedom and it doesn’t require the kind of decision-making that Sudbury students are, in effect, forced to engage in.

When I think of the Sudbury school experience, I think of it as a crucible for learning. Without handholding, without smothering, students are forced to look within for the power they need to find their place in the world. That’s hard work. What results from that hard work? As an adult who has been engaging in that kind of hard work, I can say that it has deepened my understanding of what’s important to me, and it has increased my ability to regulate myself—to discipline myself—toward achieving goals that align with my highest values. Sudbury students are given the opportunity to learn this early on.

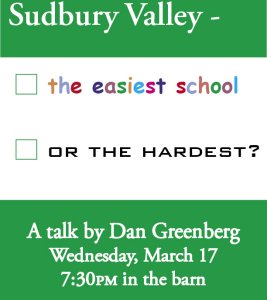

I noticed that right now on the Sudbury Valley School website that Dan Greenberg is going to be giving a talk in March, called “Sudbury Valley – the easiest school? Or the hardest?” I think I know what his answer is going to be.

I noticed that right now on the Sudbury Valley School website that Dan Greenberg is going to be giving a talk in March, called “Sudbury Valley – the easiest school? Or the hardest?” I think I know what his answer is going to be.

I’ve written before about our stint with Kindergarten. And I’ve mentioned that my kids now attend a Sudbury school and alluded to everything that’s wonderful about it. But I haven’t yet blogged about what Sudbury schooling is. I won’t be doing that today either, but I am going to tell the story of how we got to where we are.

I was homeschooled from 3rd to 9th grade. (I’ve related some of my highschool experiences already.) I’ve always been proud of the education of my youth. My mom was truly a pioneer in education. Whereas now there are homeschoolers everywhere, very few people were doing it when I was a child. My mom and a small group of other parents had convictions about education and the sort of environment they wanted to raise their kids in—and they did something about it. They pulled their kids out of school and taught them at home. I have fond memories of homeschooling and the freedom it afforded us. We could go skiing on Mondays when the slopes were clear. We could go on impromptu outings and field trips to the Science Center or play dates with our fellow homeschoolers. This experience had a definite impact on the choices I planned to make as a parent.

For one thing, I had experience with alternatives. Many people grow up without ever considering educational alternatives, but for my family, it was totally normal to do so. Just the fact that we did this—even if the education my kids are receiving today looks very different from the education I received as a child (“traditional” school-at-home)—the fact that I had this experience made it that much easier for my wife and I to consider educational alternatives for our own children from the get-go.

Since I was so fond of my own homeschooling experience, I grew up thinking I would probably do the same for my own children. When Sammy reached preschool age, we took the opportunity to enroll him at the budding preschool at our church in Seattle. We had a generally positive experience there with both him and Morgan, who attended for a couple of years also. But as they continued to grow, I continued to do research and reflection on what I wanted for my kids and whether what they were doing (preschool) was what I really wanted.

One of the things that bothered me about preschool was how set up it was for kids to please the teachers. Don’t get me wrong. The teachers were very nice and loving to the children, and the kids did love to please them. But something seemed strange and fake about this to me. I had always tried to have genuine conversations with my kids, assuming they were smart and could understand what I was saying. I would also try to speak to them as if to another adult, at least insofar as respect and honesty are concerned. I wanted to afford my kids as much respect as any other human being, and be honest with them as I would with any other adult. In other words, I wouldn’t act fake just to make them feel a certain way or get a certain response out of them. But at preschool, some of the interactions I saw—when dropping off and picking up my kids—seemed very fake to me. Teachers would act so over-the-top happy about seeing my kids arrive or tell them how cute they were. Etc. The thing that bothered me the most was how much my daughter Morgan ate it up. I didn’t like witnessing her so easily manipulated by their well-intentioned, but nonetheless manipulative, overtures.

After our Kindergarten run-in, we decided to start “unschooling” both our kids. We had been reading a few books here and there. Lisa had read The Unschooling Handbook, and I was starting to read some of John Holt’s books, including How Children Fail, which was very powerful and made me re-think so much of what I thought I knew about education. That book really got my wheels turning. I even thought I might start blogging about it (resulting in this false start)—so many were the insights and aha moments that were stimulated by reading that book. My library copy was full of little strips of paper used as bookmarks on every few pages with my responses to all the thought-provoking stuff I read in Holt’s book.

Another author that influenced me greatly was John Taylor Gatto, particularly Dumbing Us Down: The Hidden Curriculum of Compulsory Schooling and a couple of other books he wrote. I’m a sucker for impassioned rhetoric, and he had me nodding my head vigorously right off the bat. We continued to go through a phase of reading all we could about education and parenting, including other authors, such as Alfie Kohn’s exhaustively researched Punished by Rewards: The Trouble with Gold Stars, Incentive Plans, A’s, Praise, and Other Bribes. Also, Scott Noelle’s “Daily Groove” continues to be a thought-provoking resource full of helpful parenting ideas. We also attended the LIFE is Good unschooling conference a couple of years in a row and very much enjoyed ourselves there.

But we had a spur in our boot that made us want to keep looking, perhaps even beyond unschooling. Despite our misgivings, Morgan did love the social atmosphere that preschool provided. And I did see some benefit in their spending time apart from their parents on a regular basis. We had heard something about an “unschooling school” in Bothell, WA. I looked it up and read all the great essays on The Clearwater School website. I was quite inspired by what I saw. In fact, whereas I assumed Morgan would love it, I saw even more potential for how it could help my oldest, Samuel (then 6) grow through interaction with a wider variety of people, away from his parents.

So I made some more trips to the library and came home with books like Free at Last, Legacy of Trust, The Pursuit of Happiness, and Reflections on the Sudbury School Concept. These all came straight from Sudbury Valley School, founded in 1968 and the original source of inspiration for the 30+ Sudbury schools around the world. (You can get all of these books and many more at their online bookstore.) I very much enjoyed Daniel Greenberg’s scholarly look at education and what it means. Also, as one of the founders of Sudbury Valley, he had lots of stories to tell about their experiences. I was inspired—even more inspired than what I had discovered about the “unschooling” approach to education.

In fact, I was so inspired that I became a little jealous of kids who get to go to a Sudbury school, despite the fondness for my own schooling that I mentioned above. In the summer of 2007, I even started Googling for what that might look like. What would Sudbury schooling for adults look like? I searched for “synthetic village” and didn’t find much. But then one day I stumbled onto to the Clearwater Commons website, a co-housing project that some of the Clearwater School people are working on. It was then that I discovered the term “co-housing” and “intentional community” and was only a few clicks away to finding the house that we were to buy only a few months later, in Indianola, WA, home of both Wise Acres (where we now live) and The Trillium School (where my kids go to school).

Last summer, I had a chance to attend a staff conference at the Sudbury Valley School campus, and I’ve continued to be nothing but inspired by what I’ve seen. One of the most inspiring things I’ve witnessed is how dedicated the founders of various Sudbury schools are. The strength of both their intellect and their commitment is astounding. I’ve never been so exhausted after a conference. The discourse went from morning til night. I thought some of the technology conferences I’ve attended were pretty intense, but they were nothing compared to this one.

I remain fond of homeschooling, and unschooling in particular. But the Sudbury model is what inspires me. In a future article, I’ll look at some of the distinctions between unschooling and Sudbury schooling.

It’s amazing how many points there are on the educational philosophy spectrum. On one hand, you have the ultra-standardized-testing approach, and on the other hand you have something as radically different as the Sudbury school approach. My bias is clear: I see this spectrum in a sort of vertical fashion. In other words, the more a school looks like a Sudbury school, the better.

Another Trillium parent alerted me to a recent New York Times op-ed piece by Susan Engel, entitled “Playing to Learn.” It contains a lot of good insights. If I cherry-pick a bit, I can make it sound like she’s arguing for the Sudbury model. And in some ways, she is (even if she doesn’t realize it).

[E]ducators should remember a basic precept of modern developmental science: developmental precursors don’t always resemble the skill to which they are leading. For example, saying the alphabet does not particularly help children learn to read. But having extended and complex conversations during toddlerhood does.

This is a big one. How many of you parents have ever noticed your child pick up a skill (such as reading) seemingly overnight? What if I told you this is how things usually happen? In other words, we can’t see the learning. It happens under our noses. One of my favorite quotes from Voices from the New American Schoolhouse, a documentary about Fairhaven School, is this: “Learning is what happens when you’re doing something else.” (Check out the YouTube trailer for a sampling.)

And conversation is one of the main things that happens in a Sudbury school. Why? Because that’s what people do, it’s what they thrive on and learn from and grow from. So it sounds like Engel could be arguing for the Sudbury approach.

She also writes:

What they [students] shouldn’t do is spend tedious hours learning isolated mathematical formulas or memorizing sheets of science facts that are unlikely to matter much in the long run. Scientists know that children learn best by putting experiences together in new ways. They construct knowledge; they don’t swallow it.

This will resonate with a lot of people who are looking beyond traditional education. People (including kids) learn through experiences that matter to them. Knowledge is best retained when it’s relevant and has some practical application or at least some inherent meaning for the student. To demonstrate this, all you have to do is ponder this question: How much do you remember from your least favorite subjects in high school?

And:

Research has shown unequivocally that children learn best when they are interested in the material or activity they are learning. Play — from building contraptions to enacting stories to inventing games — can allow children to satisfy their curiosity about the things that interest them in their own way. It can also help them acquire higher-order thinking skills, like generating testable hypotheses, imagining situations from someone else’s perspective and thinking of alternate solutions.

Once again, play is huge at Sudbury schools. Why? Because play is huge for children. It’s amazing to witness, on those days that I’ve volunteered at The Trillium School, the complex, drawn-out games and types of play that kids will invent when they’re given a chance. They’re constantly figuring out the world around them, in concert and camaraderie with their friends. There’s no stopping them.

To me, and to Sudbury proponents everywhere, these insights clearly support the Sudbury approach to education. In a nutshell, kids are great at learning. They want to learn, and will learn. They’ll pursue what they’re interested in, which—convenience of all conveniences—turns out to be exactly what they’ll be best at learning too. Among the most important things Sudbury students learn is self-efficacy, a knowledge that they can learn, which serves them well in just about anything they choose to pursue later on, whether it be in college or not.

Ultimately, Engel is not arguing for the Sudbury approach. She’s looking for a new kind of classroom, and she has particular ideas about how to prescribe the children’s use of time:

In this classroom, children would spend two hours each day hearing stories read aloud, reading aloud themselves, telling stories to one another and reading on their own. After all, the first step to literacy is simply being immersed, through conversation and storytelling, in a reading environment; the second is to read a lot and often. A school day where every child is given ample opportunities to read and discuss books would give teachers more time to help those students who need more instruction in order to become good readers.

So it’s an incremental step toward what her insights ultimately point toward: an environment where children truly are free to explore what interests them without external prescriptions. The Sudbury model is based on several principles that go beyond what she suggests. I’ve listed some of these below, along with the methodological consequence of each:

• Principle: Each person’s education is their own responsibility.

• Methodology: Teacher-directed learning only ever happens at a student’s specific request.

• Principle: Children learn best in interaction with people of all different ages.

• Methodology: Students are not segregated by age. Think “one-room schoolhouse.”

• Principle: People are different and shouldn’t be expected to learn the same things, or at the same time.

• Methodology: There is no required curriculum in a Sudbury school.

I heartily welcome Engel’s op-ed. It’s great to see more awareness of and attention paid to the fundamental problems of traditional schooling. Her prescriptions ultimately don’t go far enough; the logical consequences of her insights, and of the science that she alludes to, ultimately point to something that looks more like a Sudbury school. But it’s definitely a start.

Off with the old, on with the new. Speaking of nostalgia, another sign that my son is growing up is what toys are striking his fancy. A few years ago—I think it was for his 6th birthday—my dad and I conspired to get him a Robosapien v2 robot. Wow, what a cool toy, if occasionally obnoxious.

Off with the old, on with the new. Speaking of nostalgia, another sign that my son is growing up is what toys are striking his fancy. A few years ago—I think it was for his 6th birthday—my dad and I conspired to get him a Robosapien v2 robot. Wow, what a cool toy, if occasionally obnoxious.  It has held up well over the years. I remember he was so excited when he got it. He made a little bed for him and named him “Botty” (short for “robot”), and put him to bed like one of his stuffed animals.

It has held up well over the years. I remember he was so excited when he got it. He made a little bed for him and named him “Botty” (short for “robot”), and put him to bed like one of his stuffed animals.

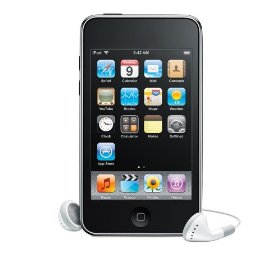

But the robot is old hat now. I recently looked on eBay and was surprised to discover that used ones are in pretty high demand, presumably because they’re not making any more of them. Sammy was already interested in selling it, and was excited to hear that he might be able to get $50-$100 for it (we paid $100 originally and new ones are now selling for $500!!). He has already saved up enough money, from gifts and allowances, to buy an iPod Touch. Selling the robot will make the decision that much easier for him.

But the robot is old hat now. I recently looked on eBay and was surprised to discover that used ones are in pretty high demand, presumably because they’re not making any more of them. Sammy was already interested in selling it, and was excited to hear that he might be able to get $50-$100 for it (we paid $100 originally and new ones are now selling for $500!!). He has already saved up enough money, from gifts and allowances, to buy an iPod Touch. Selling the robot will make the decision that much easier for him.

Selling the robot is kind of like the closing of an era for me. I won’t particularly miss its shouting and burping and farting, but I will miss the giggles it engendered in all the kids. Mostly, it’s just another reminder that life is transient, and now—not later—is the time to enjoy and appreciate and be thankful for my loved ones.